- 近期网站停站换新具体说明

- 按以上说明时间,延期一周至网站时间26-27左右。具体实施前两天会在此提前通知具体实施时间

主题:【原创】什么是科学以及我们如何走科学的道路 -- 曾自洲

按照天主教会的传统说法,耶稣基督的第一个门徒伯多禄乃众门徒之首,他于传教过程中去罗马担任了罗马教会的第一任主教。从此,罗马主教均为伯多禄的继位人,其地位因而也在其他主教之上。这便是“教皇制”的由来。所以,“教皇”的全称为“罗马教区主教、罗马教省都主教、西部宗主教;梵蒂冈君主、教皇”,亦称“宗徒伯多禄的继位人”、 “基督在世的代表”等。

在天主教会的教阶体制中,教皇享有最高的立法权和司法权,能制定或废除教会法规,指定人员组成教廷,创立教区,任命主教,而且“在伦理和信仰上永无谬误 ”。在11世纪前,教皇须经世俗君主或意大利贵族遴选或认可。尼古拉二世登基后于1059年决定教皇由枢机主教选举产生,但须得到法兰克王亨利一世及其继位者的认可。直到1179年第三次拉特兰会议和1274年第二次里昂会议两次确认后,才正式规定教皇可单由枢机主教选举产生,不过仍须承认法、西、奥三国君主对候选人具有否决权。20世纪初,庇护十世废除了这种世俗君主的否决权。1914年,本笃十五世遂成为单由枢机主教选为教皇的第一人。教皇当选后任职终身,不受罢免,但可自行辞职。

http://ask.koubei.com/question/1406121401916.html

就像中国人发家后重新续家谱一样。

中世纪的欧洲人在文艺复兴之前,那里知道什么希腊文明,罗马文明,倒是教会的楷模近在眼前。而且希腊的民主,民主有余集权不足,和西方现代国家有本质区别的。其实西方现代国家的组织形式和教会更像。

而且在文艺复兴初期,教会是起到非常多的正面作用的。

1 组织十字军东征,使得罗马,希腊文明的重新发现。

2 组织了文艺复兴的最初的研究。

西方民主起源于希腊的城邦体制。

天主教沿袭的这个体制。而且这是适合于当时欧洲的情况。当时欧洲的聚居地松散而弱小,城邦制是合适的方法。

现代西方政体多少受到这个体制的影响,可以说和希腊还是有渊源的。

假如教会有民主,那恰恰是集权有余民主不足:首先,教皇仅由各个主教当中选出;其次,教皇终身制。跟西方现代国家唯一共同点就是“选出来的”。西方国家的三权分立制度,教会里有么?跟教会组织形式最象的反倒是我党:总书记——教皇,省委书记——各地区主教,总书记也是选出来的![]()

2 组织了文艺复兴的最初的研究。

1。十字军东征本质上就是一场宗教战争,一场针对异教徒的战争。考古不是它的主要目的。正如日本侵占台湾时期,打下了台湾近现代化基础,但不能说发展台湾是战争的主要目的

2。举个例子先?看看教会是如何资助人们反对神权肯定人性的

到底是谁在乱认?![]()

希腊有两大流派,1是雅典,2是斯巴达。我们说的民主通常是指雅典。其实斯巴达也是民主,但是不是民主的主流,大家也不认他。

有关组织形式,一个是明的,就是写在纸上的制度,这个可以是假的;另一个是暗的,就是做事的方法,但肯定是真的。因为,做出来的事就是泼出去的水,假不了,而且如果组织上不支持事情根本做不出来。

雅典这种每每别人都打上门来,还要一场全民辩论的,执行力实在是有问题。在他能够利用水路的防守时,还没什么问题,一旦面临的是陆路的进攻就显得可笑了。最后希腊亡于马其顿其实是历史的必然。

而现代资本主义国家,在战争面前的高效率的一再证明,所谓民主和三权分立,不过就是一个马甲罢了。

说一点自己的理解:

雅典的民主政治权和经济权是统一的,就是说无论是政治还是经济都是民主的,权力是分散的,所谓政府在政治和经济两方面都受到极大地制约。而现代西方的民主更多的体现在政治制度上,而经济权却是高度统一的,中央政府的在经济权上拥有绝对力量或是被拥有绝对力量的组织所拥有(这个有些阴谋论的味道),而在组织形式上说就是行政权的高度统一。这是雅典式的民主所不具备的。而这个组织形式其实和教宗非常相似。至于是不是终身制倒是末节了。联想到河里所说的教宗始于罗马,而教宗对西方的影响,这也许可以相互印证吧。

文艺复兴始于十字军东征,是没有问题的。至于目的嘛,本来历史就是这样曲折的,就像当年英王签下大宪章,只是为了保住自己的位子,谁承想打下了现代法律制度的基础。

而文艺复兴初期从最重要的希腊文献,最主要的艺术家,甚至是最重要的科学家都是始于教宗,这个可以参考哥白尼和伽利略和教宗之间复杂的关系。而后来伽利略的书可以出版又是和新教在荷兰的发展有不可分割的关系。而新教和天主教之间的关系又是一团乱麻,我中有你你中有我,互为敌人又相互支持,谁知道呢。

虽然对老兄这句“而现代资本主义国家,在战争面前的高效率的一再证明,所谓民主和三权分立,不过就是一个马甲罢了”心有戚戚,但还是对老兄把教会组织形式硬套在现代西方国家组织形式上不敢苟同。

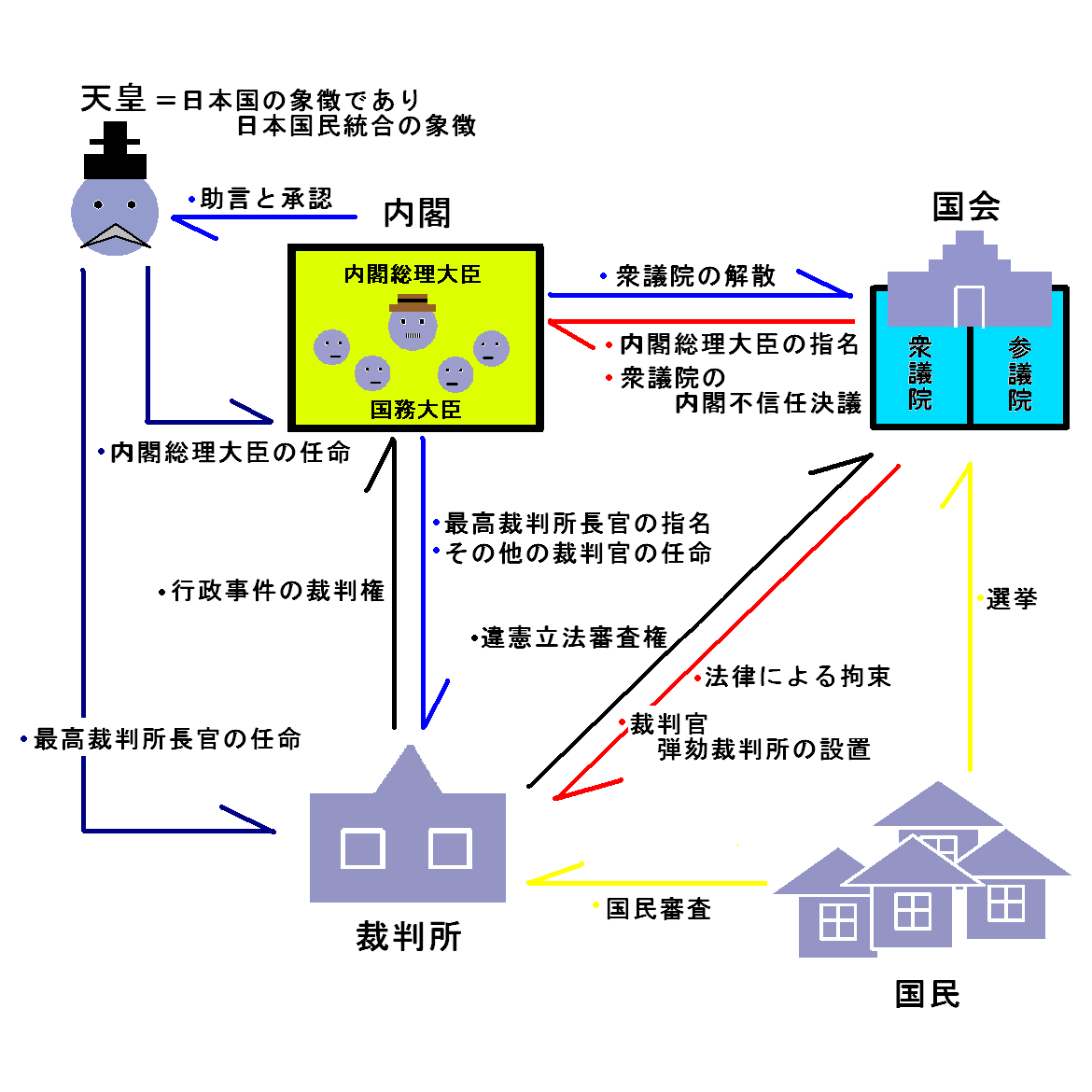

什么是国家组织形式,这个问题上我们好像是在各说各话。我认同的国家组织形式是一个国家纵向的权力安排方式和各个国家机关之间的关系,比方说

和

这是您说的“明面上”的东西。天主教组织结构网络上资源语焉不详,我能查到的是教皇-红衣主教-大主教-主教,或者您有详细地组织结构图?至于“暗的”,您给说说教廷是怎么做事的?并且除了您文中的雅典,古今中外的历代国家政府都是“中央政府的在经济权上拥有绝对力量或是被拥有绝对力量的组织所拥有(这个有些阴谋论的味道),而在组织形式上说就是行政权的高度统一”,绝非仿照教廷制度。

从教皇的产生过程看,直到二十世纪初,世俗君主对教皇人选的否决权才被取消;1914年本笃十五世遂成为单由枢机主教选为教皇的第一人。从这点上看,我是不相信宗教对现代政治制度有任何影响的。

文艺复兴的原因很多,十字军东征只是原因之一,东罗马帝国灭亡,大量人才逃往意大利同样促进了文艺复兴的诞生。老兄直接一句文艺复兴始于十字军东征未免有以偏概全,误导观众之嫌。英王签署了大宪章么……是英王打下了现代法律的基础还是大宪章打下了现代法律的基础?

至于说文艺复兴时期的文学家科学家都始于教宗,呵呵,不厚道的说,那个时候的人谁敢公开宣称不信教的话,是要上火刑架的。1615年伽利略受到罗马宗教法庭传讯,在法庭上他被迫作出承认自己错误的声明。您的论据还是支撑不了“组织了文艺复兴的最初的研究”。

西方的组织形式,大概都可以从三权分立的角度看。既然是三权分立,那么人们总认为三个权利的大小是差不多的,但是其实不然。三权中,行政权的比重远远超过其他权力。立法权,是指有议会进行立法,但是议会一年才能立几个法,基本两只手就可以数清楚了。而司法权,由于现在的官司的无比冗长,更是大打折扣,极端的例子就是印度,虽然在法院有很多很多议员的,政府官员的案子,但是每个人都是安全的,因为根本审不过来。当然西方主流的法律系统没有如此糟糕,但是一个案子干给3,5年是常有的事,如此低效率的法律系统,就算有权利,也是大大无法于行政权抗衡的。由于西方的宣传系统,很少从这方面来考虑,所以大家都认为这是天经地义的,这是社会公平的体现。其实所谓三权分立不过就是一个马甲。

而行政权在文艺复兴之前,和文艺复兴之后有很大的不同。在文艺复兴之前,领主,贵族,僧侣都有很大的行政权,而文艺复兴之后,随着民族国家的出现,行政权向中央集中,并且随着资本主义的财税制度的确立而得到大大的加强。这种制度在西方,除了在教会系统实践过,在其他任何时代,任何地点都是可以说是从来没有的。

而正是这种制度的确立,使得西方的大规模扩张有了社会组织的基础。

西方也不是没有人看的清,“迟来的正义是非正义”是上世纪初英国判例中“原创”的一句话呢。。

P:给您挑个小错,文中所有的权利都改为权力如何?

现在很多在网上争论所谓科学不科学的人,其实根本不知道什么是科学

随着时代的发展,科学至少有四种定义方式,第四种是现代得到广泛认可的定义

Today, in contrast to the seventeenth century, few would deny the central importance of science to our lives, but not many would be able to give a good account of what science is. To most, the word probably brings to mind not science itself, but the fruits of science, the pervasive complex of technology that has transformed all of our lives. However, science might also be thought to include the vast body of knowledge we have accumulated about the natural world. There are still mysteries, and there always will be mysteries, but the fact is that, by and large, we understand how nature works.

A. Francis Bacon’s Scientific Method

But science is even more than that. If one asks a scientist the question, What is science?, the answer will almost surely be that science is a process, a way of examining the natural world and discovering important truths about it. In short,

the essence of science is the scientific method.

That stirring description suffers from an important shortcoming. We don’t really know what the scientific method is. There have been many attempts at formulating a general theory of how science works, or at least how it ought to work, starting, as we have seen, with Sir Francis Bacon’s. Bacon’s idea, that science proceeds through the collection of observations without prejudice, has

been rejected by all serious thinkers. Everything about the way we do science—

the language we use, the instruments we use, the methods we use—depends on

clear presuppositions about how the world works. Modern science is full of

things that cannot be observed at all, such as force fields and complex molecules.

At the most fundamental level, it is impossible to observe nature without having

some reason to choose what is worth observing and what is not worth observing.

Once one makes that elementary choice, Bacon has been left behind.

B. Karl Popper’s Falsification Theory

In this century, the ideas of the Austrian philosopher Sir Karl Popper have had

a profound effect on theories of the scientific method.5 In contrast to Bacon,

Popper believed all science begins with a prejudice, or perhaps more politely, a

theory or hypothesis. Nobody can say where the theory comes from. Formulating

the theory is the creative part of science, and it cannot be analyzed within

the realm of philosophy. However, once the theory is in hand, Popper tells us,

it is the duty of the scientist to extract from it logical but unexpected predictions

that, if they are shown by experiment not to be correct, will serve to render the

theory invalid.

Popper was deeply influenced by the fact that a theory can never be proved

right by agreement with observation, but it can be proved wrong by disagreement

with observation. Because of this asymmetry, science makes progress

uniquely by proving that good ideas are wrong so that they can be replaced by

even better ideas. Thus, Bacon’s disinterested observer of nature is replaced by

Popper’s skeptical theorist. The good Popperian scientist somehow comes up

with a hypothesis that fits all or most of the known facts, then proceeds to attack

that hypothesis at its weakest point by extracting from it predictions that can be

shown to be false. This process is known as falsification.

Popper’s ideas have been fruitful in weaning the philosophy of science away

from the Baconian view and some other earlier theories, but they fall short in a

number of ways in describing correctly how science works. The first of these is

the observation that, although it may be impossible to prove a theory is true by

observation or experiment, it is nearly just as impossible to prove one is false by

these same methods. Almost without exception, in order to extract a falsifiable

prediction from a theory, it is necessary to make additional assumptions beyond

the theory itself. Then, when the prediction turns out to be false, it may well be

one of the other assumptions, rather than the theory itself, that is false. To take

a simple example, early in the twentieth century it was found that the orbits of

the outermost planets did not quite obey the predictions of Newton’s laws of

gravity and mechanics. Rather than take this to be a falsification of Newton’s

laws, astronomers concluded the orbits were being perturbed by an additional

unseen body out there. They were right. That is precisely how the planet Pluto

was discovered.

The apparent asymmetry between falsification and verification that lies at the

heart of Popper’s theory thus vanishes. But the difficulties with Popper’s view

go even beyond that problem. It takes a great deal of hard work to come up

with a new theory that is consistent with nearly everything that is known in any

area of science. Popper’s notion that the scientist’s duty is then to attack that

theory at its most vulnerable point is fundamentally inconsistent with human

nature. It would be impossible to invest the enormous amount of time and

energy necessary to develop a new theory in any part of modern science if the

primary purpose of all that work was to show that the theory was wrong.

This point is underlined by the fact that the behavior of the scientific community

is not consistent with Popper’s notion of how it should be. Credit in

science is most often given for offering correct theories, not wrong ones, or for

demonstrating the correctness of unexpected predictions, not for falsifying them.

I know of no example of a Nobel Prize awarded to a scientist for falsifying his or

her own theory.

C. Thomas Kuhn’s Paradigm Shifts

Another towering figure in the twentieth century theory of science is Thomas

Kuhn.7 Kuhn was not a philosopher but a historian (more accurately, a physicist

who retrained himself as a historian). It is Kuhn who popularized the word

paradigm, which has today come to seem so inescapable.

experience that it really happens that way. Kuhn’s contribution is important. It

gives us a new and useful structure (a paradigm, one might say) for organizing

the entire history of science.

Nevertheless, Kuhn’s theory does suffer from a number of shortcomings as an

explanation for how science works. One of them is that it contains no measure

of how big the change must be in order to count as a revolution or paradigm

shift. Most scientists will say that there is a paradigm shift in their laboratory

every six months or so (or at least every time it becomes necessary to write

another proposal for research support). That isn’t exactly what Kuhn had in

mind.

Another difficulty is that even when a paradigm shift is truly profound, the

paradigms it separates are not necessarily incommensurate. The new sciences of

quantum mechanics and relativity, for example, did indeed show that Newton’s

laws of mechanics were not the most fundamental laws of nature. However,

they did not show that they were wrong. Quite the contrary, they showed why

Newton’s laws of mechanics were right: Newton’s laws arose out of new laws

that were even deeper and that covered a wider range of circumstances

unimagined by Newton and his followers, that is, things as small as atoms, or

nearly as fast as the speed of light, or as dense as black holes. In more familiar

realms of experience, Newton’s laws go on working just as well as they always

did. Thus, there is no ambiguity at all about which paradigm is better. The new

laws of quantum mechanics and relativity subsume and enhance the older

Newtonian world.

D. An Evolved Theory of Science

If neither Bacon nor Popper nor Kuhn gives us a perfect description of what

science is or how it works, nevertheless all three help us to gain a much deeper

understanding of it all.

Scientists are not Baconian observers of nature, but all scientists become

Baconians when it comes to describing their observations. Scientists are rigorously,

even passionately honest about reporting scientific results and how they

were obtained, in formal publications. Scientific data are the coin of the realm

in science, and they are always treated with reverence. Those rare instances in

which data are found to have been fabricated or altered in some way are always

traumatic scandals of the first order.

Scientists are also not Popperian falsifiers of their own theories, but they

don’t have to be. They don’t work in isolation. If a scientist has a rival with a

often sent to anonymous experts in the field, in other words, peers of the author,

for review. Peer review works superbly to separate valid science from

nonsense, or, in Kuhnian terms, to ensure that the current paradigm has been

respected. It works less well as a means of choosing between competing valid

ideas, in part because the peer doing the reviewing is often a competitor for the

same resources (pages in prestigious journals, funds from government agencies)

being sought by the authors. It works very poorly in catching cheating or fraud,

because all scientists are socialized to believe that even their bitterest competitor

is rigorously honest in the reporting of scientific results, making it easy to fool a

referee with purposeful dishonesty if one wants to. Despite all of this, peer

review is one of the sacred pillars of the scientific edifice.

----Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence

本帖一共被 1 帖 引用 (帖内工具实现)

生物进化请问怎么重复验证?

并经受同行的评判和检验。

是这样的吗?好像科学很难被定义呀。

再譬如假设人是由低级物种进化来的,然后去找化石证据。

碳十四只是测年手段,本身并非重复验证。碳十四能给你重演相同条件下,生物会从最简单的蛋白质形式进化到哺乳动物?

历史学也用碳十四帮助测年,按您的说法岂非历史学也是严格意义的科学了?